Note: Much of this information comes from an official affidavit, The United States of America vs. Park Jin Hyok, also known as (“aka”) “Jin Hyok Park,” aka “Pak Jin Hek,” (United States District Court for the Central District of Caliornia June 8, 2018). If you want to review the entire 179-page document, it’s available at https://www.justice.gov/opa/press-release/file/1092091/download.

The Sony Pictures Entertainment Hack

This week, the U.S. Department of Justice announced charges against a North Korean spy, Park Jin Hyok, in violation of the following:

- 18 U.S.C. § 371 (Conspiracy), for conspiring to commit the following offenses: 18 U.S.C. §§ 1030(a)(2)(c), 1030(a)(4), (a)(5)(A)-(C) (Unauthorized Access to Computer and Obtaining Information, with Intent to Defraud, and Causing Damage, and Extortion Related to Computer Intrusion); and,

- 18 U.S.C. § 1349 (Conspiracy), for conspiring to commit the following offense: 18 U.S.C. § 1343 (Wire Fraud).

Park goes by several aliases, so he is commonly just referred to as “Park” in the official affidavit. These charges originate from a multi-year conspiracy to conduct computer intrusions and commit wire fraud by co-conspirators working on behalf of the government of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) while located there and in China, among other places. The intrusions targeted various entertainment companies, like AMC Theaters and Mammoth Screen. It also included financial institutions, and even defense contractors like Lockheed Martin. These intrusions were all done for malicious purposes, including the collection of confidential information and theft of money. However, the investigation primarily focuses on Park and his involvement in the intrusions, particularly due to the evidence collected against him. According to the affidavit, Park was hired by Chosun Expo, a company that is a front for the DPRK.

Park’s particular involvement in the November 2014 Sony Pictures Entertainment hack garnered special attention to investigators. The intrusion was supposedly a retaliatory response to a comedic film, The Interview, which was to be released later that same month. The hackers escaped with company confidential information that ultimately embarrassed Sony executives and produced major financial loss. The hack on Sony rose questions regarding First Amendment protections, U.S. government safeguards and responsibility, and the likelihood of more attacks in cyberspace.

In February 2016, Park and other co-conspirators also fraudulently transferred $81 million from Bangladesh Bank, the central bank of Bangladesh. They also engaged in similar financial heists that accumulated monetary losses into the billions and included several financial services in the United States. To this day, the conspirators continue to target U.S. defense contractors, university faculty, technology companies, virtual

currency exchanges, and U.S. electric utilities. They’ve also been accused of authoring “WannaCry 2.0,” which was the ransomware that infected systems on a global scale last year.

Of course, North Korean officials denied any involvement in the Sony intrusions despite making many public statements expressing their disapproval of the film. In fact, North Korea’s news agency called for a ban on the film, calling it “reckless U.S. provocative insanity” and even threatened a “resolute and merciless response.” The DPRK even sent a letter to the U.S. government, stating:

[T]he trailer of “The Interview” newly edited by the “Harlem Studio” of the United States has still impolite contents of deriding and plotting to make harm to our Supreme Leadership. We remind you once again that the production of such kind of movie defaming the supreme dignity that our Army and people sanctify is itself the evilest deed unavoidable of the punishment of the Heaven. . . Once our just demand is not put into effect, the destiny of those chief criminals of the movie production is sure to be fatal and the wire-pullers will get due retaliation.

“…sounds like they had a vested interest.”

Several days after the attack, file-sharing hubs were used to release confidential Sony information to the public, such as embarrassing e-mail messages, future Sony film scripts, employee medical and financial information, personal information on celebrities, social security numbers, and film contracts. In early December, Sony employees turned on their company computers to discover a threatening note warning Sony not to release The Interview. Otherwise, the release of the movie would invoke a retaliation “similar to September 11, 2001.”

“Hacked By #GOP. Warning: We’ve already warned you, and this is just a beginning. We continue

till our request be met. We’ve obtained all your internal data including

your secrets and top secrets. If you don’t obey us, we’ll release data

shown below to the world. Determine what will you do till November

the 24th, 11:00 PM (GMT).”

Five links were also provided on the infected computer screens, which were links that contained lists of files stored on Sony servers, proving they had access to the data. The infected Sony computers spread world-wide to computers in the UK and even in Latin America. Due to the widespread infection, between 7,500 and 8,000 workstations had to be disconnected from the Internet in order to contain the spread of the intrusion. Dozens of Sony Twitter accounts were also hacked. Days and weeks after, Sony executives received warning emails from the conspirators in broken English.

Half of Sony’s personal computers’ and more than half of its servers’ information were wiped as a result of a a type of ransomware infection delivered by the conspirators. The specific piece of malware used was named “Destover.” According the FBI, Destover:

contained a “dropper” mechanism to spread the malicious service from the network servers onto the host computers on the network; it contained a “wiper” to overwrite or erase system executables or program files—rendering infected computers inoperable; and it used a web-server to display the “Hacked By #GOP” pop-up window discussed above and to play a .wav file which had the sound of approximately six gunshots and a scream.

The threat by the hackers was successful and Sony suspended the release of The Interview. U.S. government investigations suspected North Korea since the plot of the movie involved two CIA agents assassinating North Korean leader, Kim Jong Un. Furthermore, the malware used in the attack bared a resemblance to similar malware used in cyberattacks executed by North Korea in the past. North Korea’s motivation behind the attack also seemed quite obvious. Despite the threatening messages, President Obama released a statement soon after stating that suspending The Interview was the wrong path to take.

The Company’s Attempt to Discourage and Reduce Incentives of Threat Actors

Michael Lynton, CEO of Sony Pictures Entertainment, sadly described the situation as it was unfolding as, “we are the canary in the coal mine, that’s for sure.” Sony largely did not know what to do and relied heavily on the FBI to investigate the attack. Lynton also described that they were so surprised by the attack that they “did not have a plan.”

Most of the actions conducted by Sony were not done to reduce the incentives of possible threat actors, but rather just to get Sony’s network back up and running for several months. It was the U.S. government that truly took the stand against the hackers.

What Could the Hackers Do with the Information and Why Did They Want it?

As previously mentioned, the conspirators stole terabytes of information regarding Sony confidential e-mail, social security number, login credentials, future film scripts, and so on. Much of this information was made public largely for the purpose of embarrassing Sony and reducing company, stakeholder, and shareholder morale.

But, the information was also used to hold Sony hostage if the conspirators’ demands were not met. Surely, the information that was released was used by Sony competitors. And since employee personal identity information was leaked, Sony was sued by several employees who claimed the company was negligent in safeguarding their private information and that the later release of The Interview put employees at risk. This should not be considered a surprise since much of the leaked employee information could be used for major identity theft schemes.

Cybersecurity Experts Doubt North Korea at First

Cybersecurity experts began debating the reliability of the technical evidence of FBI assessments blaming North Korea. Skeptics questioned North Korea’s ability to carry out such a sophisticated cyberattack and pondered if the attack was really just a “false flag” operation impersonating North Korea by disgruntled Sony employees. The attack also pointed to a hacker group called the “Guardians of Peace (GOP).”

At first, private sector analysts suggest the FBI was too quick to point fingers at North Korea. FBI investigations at the time were “flimsy” at best and experts believed that North Korea was not to blame. Many believed that an insider threat actor, on the other hand, seemed more plausible since the information stolen was located on Sony servers. And whoever stole the information had to know the names and passwords of these servers and code that information into the malware they created. In 2015, Sony conducted its own investigation with Norse, a computer security company. Overwhelming evidence of web traffic, social media posts, and Internet Relay Communications (IRC) led to a terminated Sony employee, referred to as “Lena.” Not only did Lena have access to the information used in the attack, but she also had the motive, opportunity, a deep technical background, and ties to the GOP.

Is North Korea really capable of such an attack when the country only has 1,024 IP addresses and limited broadband access? Past North Korean cyberattacks have also been limited to Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks. And placing the blame on North Korea because of its motives is not sufficient evidence. But, the FBI states that the hackers “accidentally” revealed their IP addresses several times, which were confirmed as IP addresses used by North Korea. In fact, there were two narrow ranges of IP

addresses that have been consistently linked to malicious activity associated with the conspirators. However, many cybersecurity experts believe that the “accidental revealing” of these IP addresses were nothing more but deliberate decoys carried out by proxies to blame North Korea. Most hackers carrying out an attack of this sophistication would not make such a rookie mistake to actually reveal their IP address, they argued. Threat messages left by the hackers also suggested ties to the GOP. The GOP also did not exactly deny their “involvement” in the attack. Linguistic experts also reveal that the threat messages left by the hackers was unlikely to be written by someone who speaks Korean.

Evidence Against Park, Co-Conspirators, & North Korea

However, despite what the experts suggests, and based on what the evidence shows, the FBI still has its sights on North Korea. The FBI believes that a system administrator fell for a spear phishing attack that originated from North Korea and the attack allowed the hacker to escape with login information. The hacker was then believed to map the network for infiltration. But, again, many cybersecurity experts believe that the likelihood that a system administrator would fall prey to such an attack and allow his network to be unknowingly mapped is highly unlikely. After all, system administrators are directly responsible for system integrity and assuring that everyone follows protocol. And, how were the hackers able to collect terabytes of information over Sony’s network without anyone noticing? The obvious answer would point to an inside threat actor.

Technical Similarities

The FBI, however, has its own convincing support, stating that,

many of the intrusions were carried out using the same computers or digital devices, using the very same accounts or overlapping sets of email or social media accounts, using the same aliases, and using the same cyber infrastructure, including the same IP addresses and proxy services.

The FBI also notes “technical similarities” that connect the malware used against Sony,

Bangladesh Bank, and all other financial institutions, the WannaCry 2.0 ransomware, defense contractors, and other victims. What were those common technical similarities? The FBI states that similarities include,

common elements or functionality of the malware that was used, common encryption keys used to decrypt resources associated with the malware, and domains programmed into the malware that were under the common control of a single computer or group of computers.

According to the FBI, the technical similarities were so evident that private security researchers, including Symantec, Novetta, and BAE, were able to give the group of conspirators a common name, known as the “Lazarus Group.”

Linked Accounts to Park and Conspirators

Park’s Chosun Expo accounts were also used to research hacking techniques in connection to the reconnaissance and spear-phishing attacks relating to the intrusions mentioned in the affidavit.

For example, one of the Chosun Expo Accounts tied to PARK, ttykim1018@gmail.com, was connected in a number of ways to the similarly-named email account tty198410@gmail.com—which was one used in the persona “Kim Hyon Woo.” That email account, in turn, was used to subscribe or was accessed by the same computer as at least three other email or social media accounts that were each used to target multiple victims, including SPE [Sony] and Bangladesh Bank.

Activity originating from a couple of the North Korean IP addresses were also used to access these Chosun Expo accounts for malicious activity. Based on these facts, the FBI investigations lead many to believe that Park has and maintains and affiliation with the conspirators. The use of his Chosun Expo accounts and its connection to the multiple computer intrusions is sufficient evidence to officially charge Park

North Korean IP addresses

As we’ll come to find, the use of these North Korean IP addresses is strong evidence against the conspirators. These IP addresses were used to access the Chosun Expo accounts, social media accounts, the malicious domains used in the malware, the email accounts hard-coded in the Brambul worm, the anonymous proxy service, and network scans found in Sony’s server logs.

The Brambul Worm Infections

Speaking of the “Brambul” worm, this was a piece of malware known to exist since 2009. It infects from computer-to-computer, just like any other worm; however, the Brambul worm infects computer by exploiting the victim’s Server Message Block (“SMB”) protocol. Once infected, the worm collects information on the victim, including the victim’s IP address, system name, OS, username last logged in, and last password used. The stolen information is then sent via the SMTP protocol to one or more of the email addresses that are hard-coded in the Brambul worm, many of which were created just before the Sony hack in November 2014 and accessed from the North Korean IP addresses mentioned earlier.

Three variants of the Brambul worm were found on Sony systems after the hack, which means the conspirators could easily access these e-mail accounts and retrieve the login credentials sent remotely from the Brambul worm. The information from the infected Sony systems (over 10,000 computers) were then hard-coded into a newly customized type of malware specifically designed to target Sony systems.

Identical Proxy Services

The subjects also all used the same anonymizing proxy service, which they used not only for hacking, but also to access both personal and operational email and social media accounts or to particular websites. On some occasions, the subjects carelessly accessed those accounts directly from North Korean IP addresses, while on other occasions they connected to such accounts or websites from a North Korean IP address through the same proxy service. These actions point fingers at the conspirators.

Linked Malicious Domains

Likewise, many domains were linked to the same North Korean IP addresses. It’s very common for malware to connect to infected computers via beaconing from malicious domains. The dozens of domains that were embedded in the various families of malware used by the conspirators were routinely accessed by the North Korean IP addresses through the same proxy service mentioned above.

Suspiciously Linked Facebook Pages

A Facebook page, “Andoson David,” was found to be registered to tty198410@gmail.com, which already has numerous connections to Park, according to provider records. This Facebook page was found to engage in sustained attempts to target Sony employees and personnel involved in the production of The Interview. According to the affidavit, “Andoson David” sent numerous Facebook messages to Sony employees and personnel with a either a link to the malware or a .zip file containing the actual malware. “Andoson David” would try to entice Sony employees into clicking the link or downloading the file by stating he had discovered nude photos of specific celebrities. There were many other Facebook pages registered to email accounts that were linked to the conspirators. They too sent messages containing malware to Sony employees.

Who was Park?

Park’s recent crimes are unparalleled and he has the skills to back it up. Park was college-educated and knows multiple programming languages, which he’s used for developing software and in network security for different operating systems. His skills were recognized by the DPRK, and for that, he was employed to work for Chosun Expo, the North Korean government front company mentioned earlier. This company was affiliated with “Lab 110,” which is one of the DPRK’s hacking organizations. Despite how smart he appears to be, Park made a critical mistake by using some of his Chosun Expo accounts in the computer intrusions. The FBI adds,

while it does not appear that PARK was necessarily the exclusive user of those accounts, PARK used his name to sign correspondence, in subscriber records, and to create other social media accounts in his name using the Chosun Expo Accounts. Despite efforts to conceal his identity and the subjects’ efforts to isolate the Chosun Expo Accounts from operational accounts that they used with aliases to carry on their hacking operations, there are numerous connections between these sets of accounts. Some of the operational accounts were used in the name “Kim Hyon Woo” (or variations of that name), an alias that the subjects used in connection with the targeting of and cyber-attacks on SPE, Bangladesh Bank, and other victims. Although the name “Kim Hyon Woo” was used repeatedly in various email and social media accounts, evidence discovered in the investigation shows that it was likely an alias or “cover” name used to add a layer of concealment to the subjects’ activities.

How Park and Co-Conspirators Infiltrated Sony Networks

Through carefully conducted reconnaissance, Park and his co-conspirators carefully targeted Sony employees and personnel using Spear-Phishing attacks, via social media and email messages. These messages contained a malicious payload. According to investigators,

The malware was programmed to receive commands that could be issued by the attacker that would allow the malware to collect host computer information, delete itself, list directories and processes, collect data in memory, write data to a file, and set sleep intervals.

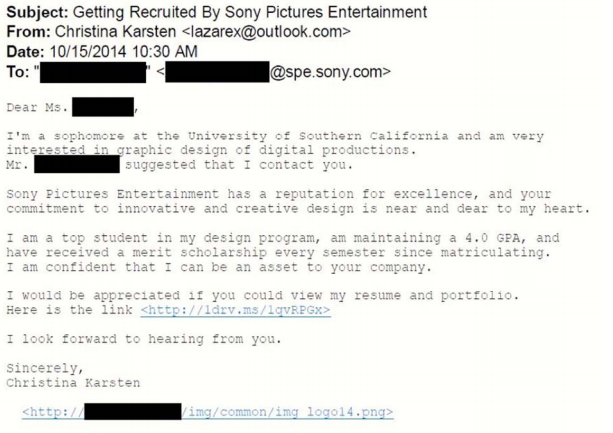

The investigation indicates that this malware appears to be how the subjects gained access to Sony’s network. Here’s an example of a Spear Phishing email that originated from an email account, ” lazarex@outlook.com.” This account was accessed using the same proxy service IP address as the other conspirators.

This spear-phishing email was sent in October 2014 and it was disguised as a fraudulent cover letter for a Sony employment request. And here’s another example of a spear-phishing email sent to look like an official suspicious login attempt from Facebook.

This actually is an official Facebook suspicious login message, except it’s just been copied and pasted. Hiding under the “Log In” button is a link to the malware that would infect Sony computers.

Announcement of Charges

With the overwhelming evidence against them, the Department of Justice will soon announce charges against Park for his involvement in the various aforementioned intrusions and wire fraud. U.S. authorities previously blamed North Korea for the Sony hack and WannaCry incidents, and it turns out that they may actually be right. However, there is still no news regarding an indictment.

Conflicting Evidence

On the night before the Sony hack, Johnson, the founder and editor-in-chief, and investigative journalist for Gotnews, revealed that 200GB of data were copied from Sony in Los Angeles; however, time stamps indicate this incident occurred in Tokyo, Japan. A Tweet with ties to the GOP in December by an American fluent in Japanese was also another indicator of an insider threat actor at Sony, but in Japan.

Moreover, an e-mail account from the GOP, “dfrank1973.david@gmail.com,” soon became a tip-off that the hacker was Japanese. Jerome D. Franklin was a popular critic of nuclear weapons. Coincidentally, Japan is the only known country to suffer from the hands of nuclear weaponry and is also the most likely country to be nuked by North Korea. Though some evidence might suggest that the attack was carried out by an insider, the attack could not have been not carried out alone.

It is also widely known that the GOP has international ties, including Japan. In addition, the GOP published a statement in 2015 claiming that the release of The Interview would harm the “regional peace and security” and violate human rights for money. The group also claims that they struggle to fight against the “greed” of Sony Pictures. All of these factors point fingers at an insider with ties to the GOP.

How the Organization Should Protect Against or Reduce Damaging Effects Due to Attempted Attacks

Sony’s original problem was “securing the human.” Humans are often the weakest link in security. If Sony employees fall for phishing emails, then this suggests that Sony should re-train its employees to withstand against such social engineering attacks. Perhaps it should also be made clear that all suspicious emails be reported to Sony’s relevant information security teams for prompt examination. This may prevent similar cyberattacks in the future/

Likewise, this problem also stems from Sony’s inability to keep its assets safe from cyberattacks. Therefore, Sony should consider investing in better anti-malware solutions that can detect unknown signatures. This of course requires moving beyond a signature-based method, which does have its own advantages and disadvantages. Furthermore, Sony should hire additional network security experts and analysts that are well-trained in detecting the types of attacks and stealth scans conducted by the conspirators.

Although this no longer appears to be an insider threat to the FBI, Sony would also benefit by investing time in creating a better insider threat policy that guarantees a high percent detection and designing hardened security assets and appliances designed to deter insider threat attempts. Keyless Signature Infrastructure (KSI) technology is a great place to start because it promises strong data integrity, evidence tampering protection, and provides “verifiable guarantees” that data has not been tampered with since it was last signed.

Some experts also suggest Sony should also consider retaliatory measures against cyberattacks and insider threats (although I’m not so sure how smart that would be). The threat of retaliation may effectively deter future cyberattacks. Additionally, Sony may also benefit, as they have already done, by investing in more counterintelligence and information-sharing capabilities. Sony understands that protections of the government extend to their company and more efforts should be taken to internationally to establish acceptable and unacceptable behavior in cyberspace.

References

Abdollah, T. (2015). Sony CEO Breaks Down Hack Response, Google Role in ‘The Interview’ Release. Mercury News. Retrieved from http://www.mercurynews.com/business/ci_27290586/sony-ceo-breaks-down-hack-response-google-role

Bort, J. (2014). How the Hackers Broke into Sony and Why it Could Happen to Any Company. Business Insider. Retrieved from http://www.businessinsider.com/how-the-hackers-broke-into-sony-2014-12

Cocking, L. (2015). Sony, Physical Access and the Insider Threat. Guard Time Retrieved from https://guardtime.com/blog/insider-threats-and-physical-access

Fitz-Gerald, S. (2014). Everything That’s Happening in the Sony Leak Scandal. The Vulture. Retrieved from http://www.vulture.com/2014/12/everything-sony-leaks-scandal.html

Haggard, S. & Lindsay, J. (2015). North Korea and the Sony hack: Exporting instability through cyberspace. Asia Pacific Issues, (117), 1-8. Retrieved from http://eds.b.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umuc.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=6&sid=d8bbc4b0-1c8e-4343-a2de-887604be3811%40sessionmgr198&hid=120

Johnson, C.C. (2014). Breaking: We Can Conclusively Confirm North Korea was Not Behind Sony Hack. The 4th Media. Retrieved from http://www.4thmedia.org/2014/12/breaking-we-can-conclusively-confirm-north-korea-was-not-behind-sony-hack/

Kabay, M.E., Salveggio, E., & Guess, R. (2014). Anonymity and identity in cyberspace. In Bosworth, et al., (Eds.), Computer security handbook (6th ed., pp. 70.1 – 70.37). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Khandelwal, S. (2018). U.S. Charges North Korean Spy Over WannaCry and Sony Pictures Hack. The Hacker News. Retrieved from https://thehackernews.com/2018/09/wannacry-north-korea-hacks.html

Shaw, C. M. (2015). FBI wrong on Sony hack. The New American, (4). 22. Retrieved from http://eds.b.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.umuc.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=fdf79e26-3d36-4463-a3da-94875c90e83d%40sessionmgr114&vid=3&hid=120

The United States of America vs. Park Jin Hyok, also known as (“aka”) “Jin Hyok Park,” aka “Pak Jin Hek,” (United States District Court for the Central District of Caliornia June 8, 2018). Available at https://www.justice.gov/opa/press-release/file/1092091/download

University of Maryland University College (2016). Psychological Aspects in Cybersecurity [Course Module]. Retrieved from the University of Maryland University Website: https://leoprdws.umuc.edu/cgi-bin/id/FlashSubmit/fs_link.pl?fs_project_id=349&xload&tmpl=CSECfixed&moduleSelected=csec620_07&cType=wbc&class=2162:CSEC620:9042:d